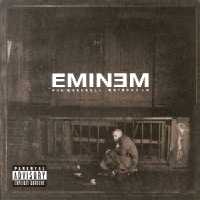

Art and Violence. On Eminem's The Marshall Mathers LP

|

It can be utmost fascinating to watch reactions to past and present art and artists, to read reviews in newspapers and on the internet, to just observe the people's reaction to something which should both never be judged by the people's reaction to it - and on the other hand, whose main attraction is precisely that reaction.

Eminem is probably the most revealing case for that dilemma: Art may be produced to be perceived by an audience, but what exactly is the role the audience is supposed to be playing? What are the preconditions, the necessary requirements an audience is supposed to possess? What is the purpose of art, if any? What qualifies as art at all? What are the categories by which art is supposed to be described, rated, valued?

This very week, a court decision relieved Oliver Stone from accusations his movie 'Natural Born Killers' could have incited real life violence. Art, as the court ruled, is considered to be treated like free speech. That gives art the protection it deserves - and desperately requires. Art must not be subjected to the criteria applying to arguments made by politicians, for instance. Art is supposed to, above other things, comment and reflect upon contemporary society. Art doesn't exist in an empty space, it is always part of the discourse of society - it is another level of political discussion. Art is always political as soon as it is released into the state, the polity, the polis. Some pieces of art may be less political, love poetry for instance, yet the Sixties might disagree in that case.

Yet what is it that art does? Is it supposed to produce something "nice", something "politically correct", something equally suitable for every possible kind of recipient? "Nice" cannot be a category for art, ever, neither is art supposed to be "politically correct". The entire notion of political correctness even has grown to be more outrageous and limiting than whatever use it could ever exert. Art must be the opposite of political correctness. The artist's role in the world is not to primarily and primitively enjoy the masses, it is to convey a unique artistic perspective via his or her work. That can mean everything between acknowledging beauty where beauty exists, as well as slapping the audience in the face.

Most great artists have done precisely that. People like Plato and Aristophanes, like Mozart and Beethoven, Tchaikovsky and Prokofieff, Dante, Poe and de Sade, Picasso and Andy Warhol, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Stanley Kubrick, David Lynch; all of those having become great through their controversiality, through changing the course of art by not obeying to "rules" established by critics, the state or the general public. True art has an edge, a dimension beyond the obvious, an outright rejection of all things considered "correct" or "nice". From a practical perspective, great art will most surely only be recognized as such by a greater public after the passage of some time. Mainstream productions without depth will disappear from the collective memory over time, unless they have been extremely popular.

Dictatorships, be they Communist, Fascist, Nazist or based upon an otherwise monarchic or oligarchic rule, are always rather restrictive in their dealings with art. Yet that doesn't exactly make democracy a liberal society, not necessarily. Democracies can be more totalitarian than any other system - by making the opinion of the majority the only valued authority. Yet freedom isn't the freedom of the majority, it is the freedom of minorites - of those too weak to prevail on themselves. The people, after having formerly suffered from tyrannic rule from above, can - after having removed the tyrant and its system - in turn create a far greater tyranny. The atrocities committed in Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, Maoist China, as well as in Rwanda and Yugoslavia, may very well have been endorsed and incited from above; yet they were executed mostly by ordinary people. The "common man", otherwise an ideal, may very well mutate into a common madman.

But this is not about actual atrocities, not about the nature of good and evil. It is about the tyranny of political correctness, of media pressure. Just critically observe the reviews. They are extremely repetitive, and they repeat always the same elements to make some stupid point about violence - which is an en vogue press topic not only nowadays, and which can stir lots of emotions. Just remember the season finale of Buffy the Vampire Slayer being delayed because of shootings at high schools - the messenger is blamed favorably, instead of taking concrete action against gun possession and access to guns, or promoting good parenting.

But that's precisely the reason why violence is maybe the key topic of art in general. Violence is a phenomenon which, while often seemingly unexplainable for political activists, is probably best analyzed by showing its effects, by delving into its abysmal dimensions and showing what's there, and then, contrasting it with the other extreme, love, with the intention to overcome the growing numbness and intellectual and artistic paralyzation of contemporary society. That's maybe the entire point behind David Lynch's work; and the same holds true for Eminem also.

But then, maybe, it is about atrocities after all, about the atrocity behind every single act of violence. But violence isn't revered or endorsed by showing or portraying it in the most extreme way; it is much more made possible by not talking about it, by not making it a subject of discussion, by not actually confronting the horror and showing the cruelty and the blood and the victim, by retreating into a "nice" and comfortable corner somewhere in Middle America, somewhere in Pleasantville perhaps. The atrocity is violence itself, the atrocity is not people like Eminem bringing it up. Showing something isn't endorsing it.

Eminem plays this game of art virtuously by using his post-modern, ironic, multi-level and multi-personality approach to the topic, by constructing himself as the madman ("Criminal", "Kill You" and "Kim") while at the same time smashing the media for their superficiality ("The Way I Am") and consequently annoying his listeners ("Public Service Announcement 2000", "Ken Kaniff (skit)") - yet there's always the ironic detachment visible, or rather, audible, which may seem somehow necessary. Yet the reaction of his fans may be more revealing than the reaction of the likes of the "Blame Canada" fraction. The most popular song on this album is "Stan", a piece dealing with a crazed and psychic fan. Here, clearly, violence is shown as negative - no playing around here, no irony - and this is the message received by the people actually listening to him.

Eminem gets down to the actual core of Rap, to its very soul - to this sublime mixture of rhythm and hexameter-like performed texts, of passages of musical beauty contrasted with textual brutality. His is a highly original approach, if you compare it with mainstream appearances like Puff Daddy. The entire album is a coherent entity, his rhythms are utterly captivating, the texts gripping and unnerving - just what today's society needs. Eminem deservedly received his three Emmys, including best Rap Album, but he should have gotten Best Album as well. This is art at its best - and most controversial.

March 25th, 2001. (first posted on philjohn.com March 17th, 2001)